I love playing games, it’s the reason I use them so much in my work. I enjoy unlocking patterns within games and I love the social interaction that is part and parcel of really good games. The ones I really enjoy are the ones where I learn something. Even if I only realise later.

Game-ify everything

It’s become something of a “thing” over recent years: if you want people to engage with something then make it a game. Or Gamify it. This is usually applied to games in the digital realm, which is great, but there is a special kind of magic that happens when people play together in the real world.

That magic is what gives people the kind of memorable experiences that I trade in. When it works, it gives me a kick every time.

So, when I’m asked to design things, I often turn to making a game out of it. It’s been fruitful and very rarely lets me down.

Kings of Coal

One of the very first pieces of design I ever did for a museum was back when I was a learning officer in Hartlepool. The brief was simple: we want something Hartlepool focussed, where families can take part together and does not need a member of staff.

So I built a pair of board games. One of them required you, literally, to take coals to Newcastle (well, Hartlepool & the Tees Valley, but bear with me). I was really pleased with it: the idea was to draw attention to the coal rush that made Hartlepool a boom town. It wasn’t desperately popular, but then family learning week was an odd thing. I’ve just dug it out, it hasn’t aged well and I wouldn’t be nearly as proud of it now. I suspect that the strongest part of the game was the taking “coals to Newcastle” bit.

But, I’d been well and truly bitten by the games for learning bug. It’s a thing I kept coming back to.

It’s a game where you play a role…

Whilst I still enjoyed playing and using those classic bard-style games, another of my gaming passions was better suited to designing learning experiences. Playing a role. It probably doesn’t even feel like a game when you’re playing (and theorists still argue vehemently about the role of the game in roleplaying games).

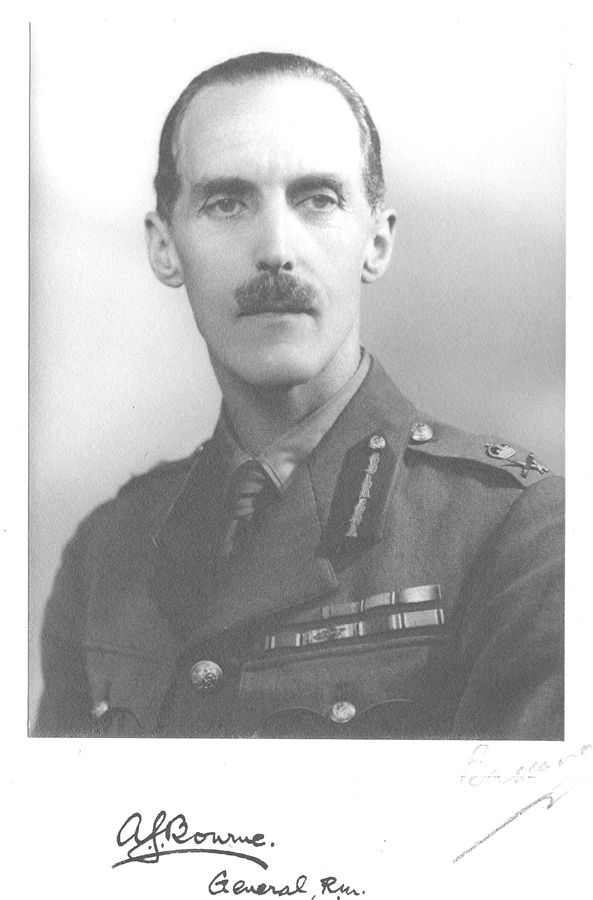

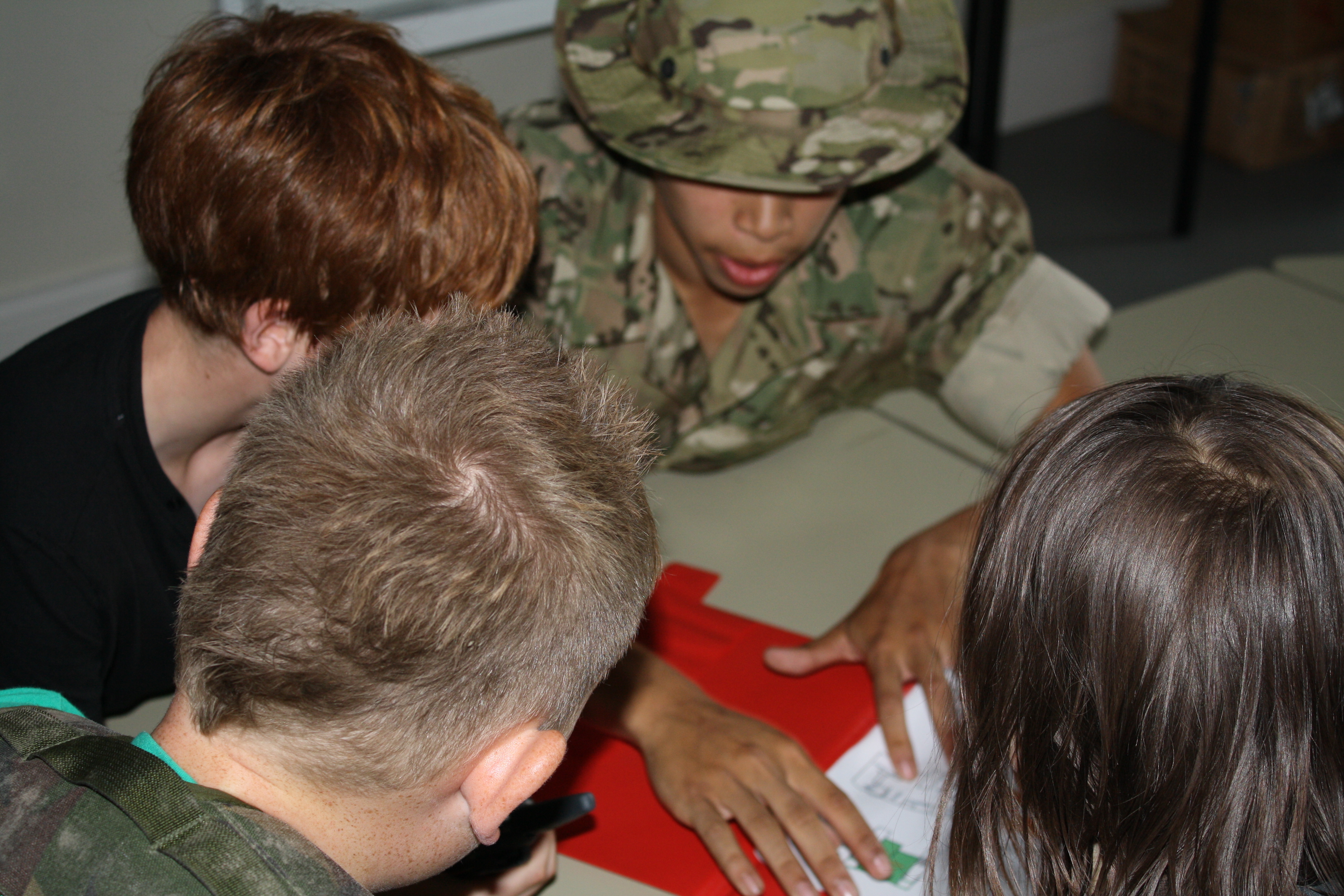

During my time at the Royal Marines Museum our family provision evolved very quickly into something quite unique. Every session we ran, participants played the roles of Royal Marines on a training exercise. They were immersed in the experience through dressing up, a formal briefing and, crucially, consequences. They learned all sorts of skills including planning, communication, teamwork, decision-making as well as gaining an understanding of the experiences of service personnel when deployed. Some of those scenarios became classics and were used with all kinds of groups from schools to staff training. The VIP close escort scenario gained the seal of approval from a Marine who had just returned from the exact same training exercise as part of his work.

Roleplay fun

These kinds of games can be very powerful and, when deployed appropriately can give a real insight into other people’s experiences or understanding why they make certain decisions. I used roleplaying scenarios for understanding how the Nazi Party came to power and the role of the Army in Northern Ireland. These were not laugh-fests, but created some very powerful and moving learning experiences.

Re-skinning

I found myself immersing myself in the theories of game design and game playing. I’ve probably learned more maths from understanding probabilities and balance for games than in doing my accounts. The split between crunch (the rules) and fluff (the setting) was part and parcel of my daily thinking as was the GNS (and later Big) model of games, both were built into my planning tools.

I ended up taking these planning tools on the road and using them to spread the word about how powerful these games could be in teaching. I presented at conferences and gave workshops where I took people through this design phase to show how they could make their own games. I recall there were all sorts of odd games designed at these sessions, including one about the etiquette of golf and one about coal miners in their canteen.

RPG Planning sheet

It showed me that this kind of learning scenario can be turned to seemingly unlikely situations. Not only that but they can be incredibly successful.

Tell my story

One odd way in which games can really boost learning is in stimulating creativity. I love telling stories, it’s what I do for a living (amongst other things). I know that many people find it difficult to be confident enough to share their creativity, I know I suffer crippling stage fright before playing music or singing in front of people.

So, when I was asked to create something that helped teenage boys with literacy, this seemed the perfect opportunity. Out came the planning matrix and off I went. I’ve talked about the results in this blog, but the short version is that we created a scenario where the boys foiled a terrorist threat the museum. All they had to do was decipher the clues and do some writing of their own to get the next one. We never phrased it as that, but that’s what they had to do. It was brilliant.

Now tell me yours…

More interestingly, the following year we were asked to create something about ghost stories…No pressure. This is where the first of my collaborative storytelling games came to life. One of the big issues with asking people to be creative is that they get “blank page paralysis” so a good game will give structure to what they have to do. The other, especially with teenage boys, is the fear of being rubbish and being laughed at. So a good game will have rules to prevent that.

In this case, they were given a character archetype for a ghost story (such as the high-school jock, the geek, the ex-convict) to prevent them having a blank page. Each of them had to create a secret that their character had that they didn’t want anyone else to know about. Simple: what might your character have done or seen that they didn’t want anyone else to know? If they were stuck then the table could help them out. The rule here is that no idea is rubbish. If you don’t like it, you can only suggest a way of improving it (“would it be better if…”).

Then the first kicker. The person to their left was involved in that moment. It’s up to them to come up with how and then agree with you. Suddenly these characters are tied together by secrets. This way both of you are involved and probably neither wants anyone to know.

The second kicker is that the person to their right knows about it. How did they find out, what have they done about it and why haven’t they told anyone else?

Now you have a table of characters who are tied together by secrets and lies. Sadly, this was all we had time for. They went back to school to write their stories.

We can find a game anywhere

Surely, there must be a limit to this approach? There is. It’s that you have to give people the knowledge and information they require in order to take part. This is where museums are really strong.

Once you have that, the approach can work in surprising ways. You want me to use a roleplaying scenario and game to teach engineering in a way that engages unusual audiences? Have a look at the humanitarian scenario created for Aldershot Military Museum, where they used the museum’s collection to build their own vehicles that could be used to get emergency aid to villages cut off by a volcanic eruption. Yes, really.

Now, with driver

You want me to use this to understand the form and significance of Bronze Age burials? Then the work I did for the South Downs National Park’s Secrets of the High Woods project will be right up your street.

You want a session where you learn about programming robots? Then maybe a trip to the National Army Museum for their On the Move session is in order.

You want a game that draws attention to the violence in the suffrage campaigns of the early 20th century? Actually, I found this today from 1908.

You want me to help you embed learning on a subject by encouraging creativity? In that case, take a look at my storybuilding workshops.

You want something different from all of these, or something a bit like it only different? Give me a shout and I’m sure we can work something out.

Game over: Lessons learned

So, after all these years, have I learned about designing learning games and game sessions?

- Always have multiple solutions to a problem. That way people can be creative and succeed in ways that will surprise you.

- Success makes people feel good, it’s not a test of how good they are. So make success happen, eventually. Unless the difficulty is the point (in a game where you highlight why people have made poor choices).

- Be prepared for running these sessions to be exhausting.

- There’s no such thing as a bad idea, but sometimes you won’t be able to make an idea work. Put it down, file it and know where it is when the situation arises that it will be useful.