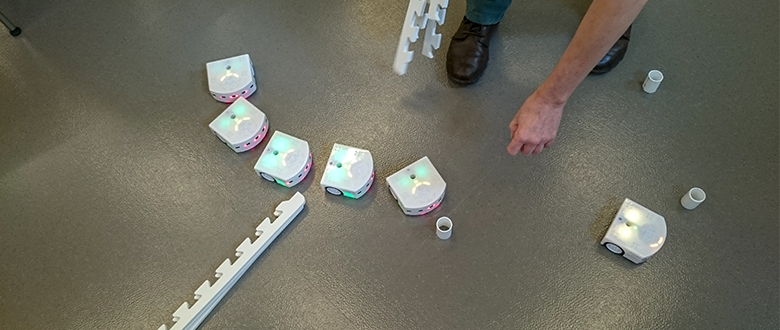

Here is a picture of my study last night: There are piles of floor tiles everywhere, a load of gaffer, a tape measure and a craft knife. Oh, and there’s a robot on the floor as well. So, what on earth is going on?

Robot study

This is what the office looks like when I am getting ready to deliver a new session. This is what it looks like when I am creating the new materials for school sessions. I love this stage of creation: there is a real sense of things coming together and, finally, I get to see something in reality that’s been existing in my head (or on my computer) for a while. I really enjoy that feeling of creating something real. In reality, this scene is a very long way into the project, so it may well be instructive to know how I got here.

Way back, in the depths of time

This all began as a session that a client wanted to run in their museum. They came to me with a loose idea for a session based on robot programming for primary school children. What they wanted me to do was turn it into something real, something cool and something that works. No pressure.

Once we’d chatted a little, they sent me a consignment of their robots by courier and let me crack on with it.

Robot consignment

The robot is created by a company called Thymio, it turns out they have a series of modes. They respond to the outside world in different ways depending on what mode they’re in. That’s cool but pretty limited. If you’re feeling more advanced they can be plugged into a computer and then you can really get inside them. They have a visual programming language (or VPL) so you can give them a series of “when, then” statements and then set them running. This is a lot of fun to tinker with, and fairly easy to understand what you would like to accomplish. I ended up tinkering with this for a while and getting really excited about the scenarios that we could play out with them.

Then I tried to get them to do something specific and realised that it’s far from straightforward. In fact, it’s downright tricky.

A return to the spec for the session reminded me that, not only was the session for KS1-2 (Primary) so I might be getting 5-6 year olds taking part, but it was only supposed to last an hour. Back to the drawing board.

Meanwhile, back at the plot…

So, what can we make for a group of primary school children? The session is for a military museum, so we’re really talking about how the military uses robots…hmmm…

Back to those six modes, and see what we can do with them? And then my creative juices got going. What scenarios could I create where the robots, with their pre-programmed modes, would be able to carry them out?

1 yellow mode, several green mode

They have a mode that responds to clapping. You clap a certain number of times to make it do different things. Except when there is background noise like you might get in, say, a room filled with 30 odd primary school pupils. So, maybe not that one, then.

How about the one where you press buttons and it does what you tell it? Rather like remote control, only not remote. Probably not that one either.

Aaah, there’s a mode where it moves forward until it sees and obstruction then diverts to go past it. Now we’re talking. Hmm, is there a scenario..? How about a minefield? The robot needs to find a safe route through the mines by detecting them and diverting until it gets to the end. That has legs. That could be a lot of fun. That can be run with.

There’s also a mode where it will follow a black line on the ground. What can we use that for? I know: those black lines could be streets in a city, that cross each other like a maze. The mission is that they need to find a way through the city by using the robot without any people there because it’s too dangerous. This is beginning to come together. I like this pair of scenarios. They can work for wee ones because there’s no programming, but they’ll work well for older ones because they have to make a number of decisions that can materially affect the outcome.

Source material

Now, where does one buy a minefield from? Or some kind of giant city map where the roads are black and the background is white?

The answer, as is often the case in this business, is that don’t. Instead you create them out of other things. I can make round obstacles out of some white plastic piping that I have in the “workshop”. If I saw it into 5cm lengths I’ll have loads of them.

robot minefield

That’s that sorted. Now for that road map…

The client wanted it as big as possible, but they want it to go back in the cupboard at the end of the session and I’d like it to be modular so it can be adapted and more easily stored. Right, ok. So, basically, I’m looking at creating a giant jigsaw. Now, you can’t just pop out and buy a giant jigsaw with roads on it. Well, you can but it’ll cost you an arm and a leg. So, how can I construct something that fulfils the same role? Got it! Blank tiles that fit together and mark the roads with gaffer tape. A quick bit of playing revealed that there are only a few possible layouts for each tile so I can make several of each, which will result in all the options you could need.

Which lead to the situation in the study you saw above, making enough pieces for a jigsaw that’s 3m by 2.5m when laid out. All that’s left is to measure, mark, stick and cut that tape. This is important because the roads need to match up from one tile to the next, otherwise the robots won’t be able to follow them.

robot roadmap

Disaster strikes!

Testing is always important. Testing shows up flaws that are unexpected.

This is no different. In this case it relates to the right-angle bend tiles. It turns out that, when faced with a dead end (which is what a right-angle bend is to them) the robot will always turn right until it finds a new way forward. Thus, when faced with a 90 degree corner to the left, the robot will turn right until it’s turned right the way round and duly headed back the way it came.

Bum.

Ok, big fella. Think about it for a moment, there must be a solution…Bear in mind at this point, I’m part way through taping up the tiles, so there’s not a lot of slack in the timescales.

Hmmm…What if the bend was two 45 degree turns rather than a single 90 degree one? Might that work?

Ok, tape it up, see what happens…Success! We’re back in the game.

Contact with the enemy

The next morning, I found myself crossing London with 32 foam tiles, 8 robots and about 40 “mines” in addition to such niceties as “lunch”.

Which was a challenge.

There is a saying in the military: no plan survives contact with the enemy. That could well be said of lesson plans and children. Which is why we pilot these things.

Was I nervous? Yes. In theory, everything should work. Practice is not theory. Everything could fall apart around my ears.

Setting up on my own, waiting for the class to arrive is always a fun time.

I needn’t have worried though. Almost everything went as planned.

They were able to do the first experiment: to work out which mode was which.

The clapping mode was an utter disaster in a room full of children. That was what I expected. The other modes worked fine (though the “purple” looked blue and the “blue” was very much cyan, which caused a few issues).

They (mostly) managed to make their robot navigate the minefield.

They even managed to use the robot to rescue the wounded soldier (artist’s model) from hostile territory (those tiles I spent ages putting gaffer tape on).

Everyone was happy.

And it finished on time.

I got to walk home without all that stuff.

Right. Let’s try to break the robot

Following that we got the team together, along with volunteers, so I could show them how it all worked.

And we did the most important testing (after letting children loose with it), and that’s stress testing: where you deliberately try to break something by doing it wrong or seeing if you can use the wrong answer to still get to the finish.

This is often a lot of fun, so long as you don’t identify any fatal flaws. Sometimes you discover a loophole and deliberately leave it in as a reward for creative thinking. In this case we discovered it was possible (just) to successfully navigate the minefield by putting your robot behind someone else’s and setting it to “follow” mode. We left that in to see if anyone thought of it.

Walk away

There comes a point in this process where you just have to put it down. Where you have to walk away from the thing you’ve invested time, effort and creativity in. It’s not mine any more, it’s theirs. They will use it and deliver it as they see fit.

I will probably never see it again.

And that’s quite sad

Until someone asks you to do something else cool…

…You want me to make an event where we tell the story of tank battles using radio-controlled tanks?

“Quick! To the bat cave! I have an idea!”

Tank testing

Opening the box

Opening the box Eitech tracked vehicle

Eitech tracked vehicle

Bucket!

Bucket!