A tale of how something else awful became part of my teaching practice. Or, how anything can have a sliver lining professionally. Eventually.

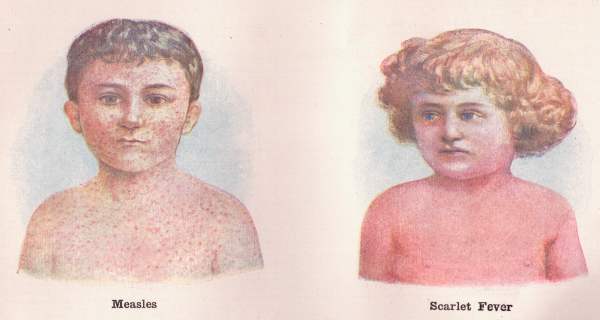

Some months ago, I wrote a post about how I caught scarlet fever. I described it as the worst CPD ever.

Apparently, I was in error. I had forgotten something far worse. It became relevant to my teaching for the first time ever last week.

So, here’s another tale of gruesomeness and how it became grist to my learning mill.

Inspiration in even the strangest places

recently, I have found myself teaching a session at the National Army Museum about prosthetic limbs and robots. The session is fairly straightforward: it looks at soldiers who have prosthetic limbs and asks the children to carry out a simple task using a robot arm. The children are asked what task they think soldiers would feel most of a sense of independence from being able to carry out without assistance. Invariably the children (or, in one case, the teacher), identify going to the toilet. That’s not the task.

The simple task is to make a cup of tea. It’s not as easy as it looks, which is rather the point.

Being put on the spot

In the course of delivering one of the sessions, a child asked me whether I have any prosthetics.

A reasonable question, I suppose. After all, how can I speak from a position of knowledge if I have no first-hand experience of the situation?

I looked at myself and admitted that I was largely complete, but carried on to talk about the work I have done with Hasler Company, the Royal Marine rehabilitation unit (now officially Hasler Naval Service Recovery Centre), and how I had worked with and come to understand the issues and emotions of service personnel with life-changing injuries.

It felt like a bit of a soft answer, but they seemed happy with it. Anyway, they enjoyed the session and went away happy. Besides, I can’t beat myself up for not having experienced everything I teach about.

Hang on a minute…

At the weekend I was cooking roast duck. I tasted the juice coming off the bird with a spoon. A spoon that had been dipped in fat from an oven set to 180 degrees. “It’s a good job,“ I thought to myself, “that I don’t have my real teeth any more. This would probably be really hot if I could feel temperature.”

Then I paused and considered that thought: “It’s a good job I don’t have my real teeth any more.”

Oh.…real teeth.

Wait a moment. Does that mean I have prosthetic teeth? Yes, I think it probably does. I did lose them in a life-changing incident and they’re never growing back.

How does one “lose” teeth?

In the summer of 2002, I was in a road traffic incident where, to cut a long story very short, I collided with a Land Rover when riding my bike. The slightly longer version is that the driver overtook me and then stopped very suddenly, so I crashed into the back of the car, taking out their back windscreen with my face.

Or, at least, that’s what I’m told happened.

I remember trying to work out where my glasses had gone because I couldn’t see.

Then I was rushed to hospital by ambulance and straight into A&E. A battery of tests, x rays, scans, some maxillo-facial work and a lot of stitching later I was sent to bed on a ward. It turns out I was lucky to come out of it in one piece.

In the days before omnipresent mobile phone ownership, getting a message to my family was…tricky.

It looked a little like this

It wasn’t until the following morning that I was even allowed to look in the mirror. I discovered that, although I hadn’t broken anything, my face was a mess. In fact, I looked a lot like Robert de Niro when he played Frankenstein’s monster. It was not a pretty sight.

And I couldn’t speak. That was mostly because I’d knocked out several of my top teeth in the impact. Others were glued in place in a desperate attempt to save them.

Later that day, I was sent home with instructions to take it easy. That wasn’t difficult: I felt like I’d been hit by a car.

Within a fortnight it became clear that all of my front teeth at the top were either gone or going go. I was fitted with false teeth: dentures.

Dentures!? I was 25. People my age are not supposed to have to buy strident and denture glue. On a number of occasions, I was actually asked if I was buying them for my gran. Nothing is guaranteed to make you feel old better than that.

Dentures are rubbish. They never feel like they belong. They have an annoying tendency to fall out when you least need it. I will never forget the look on someone with whom I was sharing a climbers’ bunkhouse when I produced a glass while brushing my teeth and proceeded to spit my front teeth into it. Talk about mood killer.

The long and short of it

I had the dentures for a year. A year of hospital visits, of long sojourns in the dentist’s chair and painful procedures.

At the end of it I was the proud owner of a bridge. It’s basically a set of false teeth that are glued in place, stuck over my canines.

I’ve had them for fifteen years now. Most of the time, I can almost forget they are not my real teeth. They don’t hurt and they fit pretty well, all thigs considered. I’ve had to relearn how to whistle, how to eat apples, in fact anything hard, I have to be careful with drink because of the odd shape of my lips, I can tell when I’m dehydrated because the bits of road in my lip come to the surface, things like that. I can no longer do my party trick of picking up a full glass of drink with my teeth, the bridge is too expensive.

This is from an entirely different incident

They feel almost “normal”. Almost. Most of the time. Sometimes, it feels like I’m wearing a gumshield. After all this time, I usually forget that this isn’t the way I have always been. Except when I try to whistle.

So, I don’t consider myself an amputee. That would be greatly overstating it.

But, there is less of me than there used to be. I have had to get used to the fact that by body is different, that I look different, that a part of me is artificial and might break in normal use. Thinking back on it, there was considerable emotional adjustment.

Back to the point

Where were we?

Oh yes. If I dig a little, I do have some insight into what it feels like for a catastrophic (potentially fatal) incident. It’s an insight that I can bring to bear when teaching about traumatic experiences. So, next time I am teaching a class and someone asks that difficult question, I will have to remember to say yes. It will make my teaching better.

I would not recommend this as a way that anyone else can hone their teaching craft. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy. It was awful, but it has helped me.

Just like the Scarlet fever, you will be pleased to know that I have no plans to use bloody pictures of my own face to illustrate learning sessions.